By Donald Hagerty

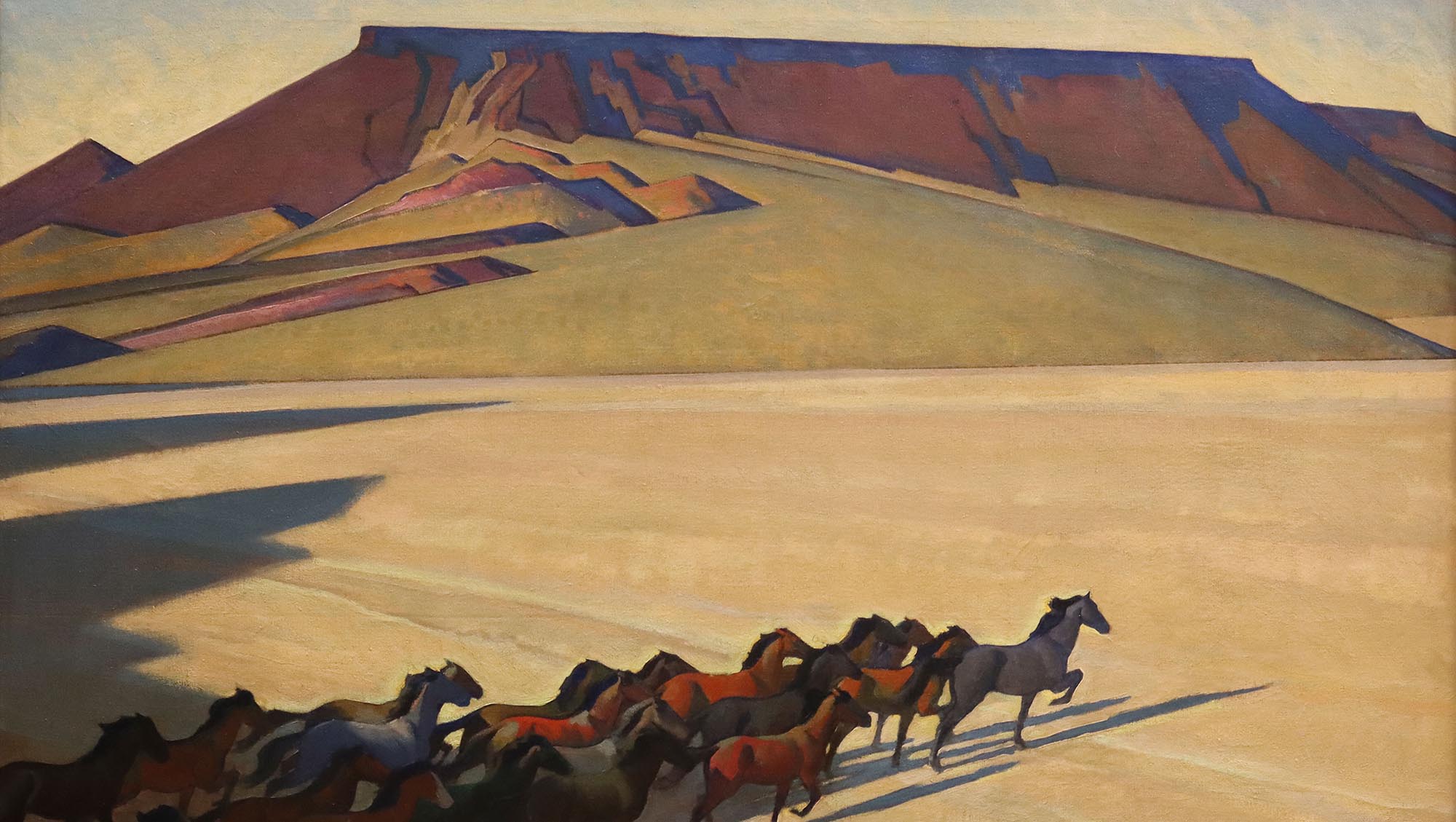

forward from Mesas, Mountains & Man: The Western Vision of Maynard Dixon

catalog from the 1998 Maynard Dixon Exhibit at Medicine Man Gallery

By the end of World War I and after, San Franciscans were used to seeing a figure in a distinctive black suit walking down Montgomery Street. Sometimes a waiter from the Black Cat restaurant would call out, “Morning Mr. Dixon. Cold fog.” “Cold as Christian charity,” might be the response as Maynard Dixon headed toward his studio on Montgomery Street.

Sometime if you visit San Francisco, walk down Montgomery Street and stop at 728. This building and several others along the block survived the 1906 earthquake, frequent remodeling, and date from the early settlement of San Francisco. In the years between the world wars, writers, artists, and craftsmen burrowed into these narrow brick structures. In those days there was nothing romantic about their ventilation, crumbling plaster, dark, dank stairways, or ancient plumbing. During the 1920s and 1930s, the building could be entered through a tall green door, the peeling paint offering glimpses of earlier eras. Never locked, night or day, during the depression years jobless men sometimes slept in the hallway at the base of the stairs. On the first floor wall, nameplates identified tenants, some handwritten, but most represented with elaborate care in highly individual designs. One of them showed an Indian Thunderbird captured in a circle. Maynard Dixon, it read.

Dixon’s third floor studio seemed saturated with cowboy and Indian artifacts; Navajo textiles, baskets, Pueblo pottery, saddles, lariats, bridles, a feathered Plains Indian headdress, hundreds of his drawings scattered about encompassing the history of the American West, and a number of Dixon’s sundrenched, colorful, and boldly designed paintings. Over the door, a bleached buffalo skull mounted on a blue circle greeted visitors.

Maynard Dixon seemed an incarnation of Owen Wister’s The Virginian. Slender, almost angular, thin-faced with deep blue eyes, he had dark hair cascading toward one eye, rakish mustache, a slightly hooked nose, and long, slim, facile hands. As he worked on a painting he might sing a Navajo chant or Mexican song, and amaze visitors when he rolled a cigarette with his left hand. A tailored black suit, with black, wide-brimmed Stetson hat and hand-tooled, high-heeled cowboy boots accentuated the effect. His step was light and careful. “Walks like a deer,” someone once said, each step answered with a faint, ominous buzzing by the rattle still attached to his rattlesnake hatband. Usually clutched in his left hand as he walked down San Francisco streets was an ebony swordcane, tipped and headed with silver, embedded in the handle the same Thunderbird which appeared on his studio address nameplate.

Born in 1875, Dixon grew up in the landrush boomtown of Fresno, California. A sensitive, frail youth who listened, looked, and never forgot, Dixon early on was impressed by the horizon line on the open plains of the San Joaquin Valley. Long horseback rides over the prairie transfixed his mind with the dead level, an endless horizontal plane forever radiating in all directions. This far horizon, the big bones and long lines of the land would become a Dixon signature in later years. “No doubt, he once recalled, these flat scenes have influenced my work. I don’t like to psychoanalyze myself, but I have always felt my boyhood impressions are responsible for my weakness for horizontal lines.”

Part city-living bohemian, traveler on desert landscapes, sometimes a mystic touched by the reverberation of unknown presences, Dixon became, for much of his life, one of those solitary desert pilgrims, trying to bring back through his art testimony and inspiration from the deliverance of space, the wisdom of the ground. From 1900 to his death in 1946, he roamed the West’s plains, mesas and deserts by foot, on horseback and buckboard, and ultimately, the dreaded automobile, drawing, painting, and expressing his creative personality in poems, essays, and letters, searching for a transcendent awareness of the region’s spirit.

By the early 1920s, Dixon would work out painting techniques to express the West as he felt it should be but discovered it changing under the impact of popular culture. Henry Ford, the Model T, and Hollywood had stolen the Old West away. The inexpensive automobile was destroying the isolation of even the most remote communities, emptying the stables and dousing old campfires. The motion pictures started imitating the Old West then the Old West began imitating the movies. The Old West was departing on horseback, a New West arriving by automobile. Maynard Dixon did not like what he saw coming.

Heonce declared, “My work, outside the limits of illustration, is not the regulation “Wild West” type painting. I aim rather to interpret the vastness…loneliness, and the sense of freedom this country inspires. To me, the wind of the wastelands has color, the opalescent ranges of the desert seem like music, and sometimes the giant clouds of storm, piled far above the mountains, take form as lost and forgotten gods…” Dixon loved the land so deeply, it seemed, he no longer knew where Maynard Dixon ended and where the West began.

Central to any discussion of Dixon’s art is the consistent relationship of nature to his work. “Nature, he would declare, is your starting point. You have eyes to see, nerves to feel, a mind to understand. Have respect for nature and your natural responses. Study the things that interest you, that awaken your imagination and nature will keep you sound.” The eternal Western landscape served as Dixon’s reference point in an ever-changing world baffled by technological discoveries and the growth of an urban tradition.

Central to any discussion of Dixon’s art is the consistent relationship of nature to his work. “Nature, he would declare, is your starting point. You have eyes to see, nerves to feel, a mind to understand. Have respect for nature and your natural responses. Study the things that interest you, that awaken your imagination and nature will keep you sound.” The eternal Western landscape served as Dixon’s reference point in an ever-changing world baffled by technological discoveries and the growth of an urban tradition.

To reach this vision, Dixon painted most of his larger canvases, those twenty five by thirty inches and larger, in the studio after his return from a trip, working from drawings and field sketches, direct response from his natural surroundings. He always kept little pads of special drawing paper of different colors and sizes in the roomy pockets of jackets. Dixon would make hundred of small drawing and color sketch note on one of his trips, annotated with the year, place, sometimes with color noted in words. His hand and mind worked together in the drawings, storing images which served as a genesis for paintings or murals. Besides drawings, he often did oil field sketches, some highly finished, others quickly rendered. Once back in the studio, Dixon would review the drawings and oil paintings, seeing them with fresh eyes, then place them in groups; one for large important canvases. another sold as sketches, and the third group destined for destruction, as not worth using. A painstaking, thorough worker, Dixon charted a deliberate and careful approach to the construction of a painting, consistent within the framework of his personal convictions.

When Dixon went on his extended trips to the desert, he started in late summer when the monsoons brought architectural cloud worlds, or in early fall when the edge of autumn began, when the cottonwoods started turning that impossible yellow, bright flashes tracing desert watercourses, when the sun, lower in the sky, throws long angular shadows across the landscape. “As to my techniques, he once said, it is no accident, and is developed to meet my needs. My feeling is toward the thing I do, and austerity and clear definition are the dominating character of the arid lands I work in.”

Dixon’s symbolic responses to the West’s landscapes and cultures found their way into his paintings. The cottonwood tree, for example, appeared with increasing frequency after 1930.

When enough frosty nights have accumulated in early autumn, cottonwood foliage turns from bright green to a shiny yellow-gold, the glittering trees visible from great distances on the austere landscape. A seasoned traveler in the West’s arid lands, Dixon understood the cottonwood’s promise; its leaves, rotating and rattling, might foreshadow rain; its figure on the horizon was a signpost for water, firewood, shade and shelter. The cottonwood stands alone or in small groves along watercourses. It prefers solitude, as did Dixon himself. He made the cottonwood a personal symbol in his art in the last fifteen years of his life, painting many canvases of a tree which tolerates little between it and the sun and wind.

Willa Cather wrote that cottonwoods are wind-loving trees whose roots are always seeking water and whose leaves are always talking about it, making the sound of rain. The Lakota Sioux refer to the cottonwood as the “dreaming tree,” a place for visions. Perhaps Dixon now saw a new vision of the American West, a place populated by phantoms dying of nostalgia and bitterness from the changes, shivering and clattering among the leaves of old cottonwoods.

Maynard Dixon died in Tucson, Arizona on November 13, 1946. His devoted third wife, Edith Hamlin, printed a small two-page announcement about his passing, on it Dixon’s longtime companion, the Thunderbird, and one of his poems. In the spring of 1947, Edith carried Dixon’s ashes up to their summer home in Mount Carmel, Utah, scattered them on top of the sagebrush and juniper-dotted ridge behind the house, then installed a bronze plaque which reads, “Maynard Dixon, 1875-1946.” Westward lies Zion National Park, beyond that the silent vastness of the Great Basin. Maynard Dixon country.

Permission to reproduce photos and paintings in this online catalog secured by J. Mark Sublette. All rights reserved. No portion of this online catalog may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from J. Mark Sublette, Medicine Man Gallery, Inc. Photographs courtesy John Dixon.