Reprinted courtesy of Southwest Art (Oct 1999)

Legendary western artist Maynard Dixon [1875-1946] spent his final years in Tucson, AZ. Today, more than 50 years after Dixon’s death, Mark Sublette, owner of Medicine Man Gallery, has found a way to memorialize the master: An entire room in the gallery is dedicated to Dixon’s legacy. A number of his bold, sun-drenched paintings, drawings of the American West, and personal mementos hang on the walls or rest in glassed-in cases; reminders of Dixon’s strong affinity for Tucson and southern Arizona are evident throughout the collection.

Dixons propensity for chronicling the events of his time can be seen in many of the works in this room—in two preliminary sketches for one of his famous Depression-era works, Scab, and a study for another important painting, Earth Knower. Numerous drawings range from the early 20th century to Dixon’s final years in Arizona. There are several framed Dixon poems, including the poignant At Last, all written in the artist’s expressive hand. Though there are always some paintings and drawings for sale, much of the work is from Sublette’s personal collection or on long-term loan from private collectors and members of the Dixon family.

Maynard Dixon Museum, Tucson Mark Sublette Medicine Man Gallery

The concept for the room evolved out of a major retrospective on Dixon’s work that Sublette mounted in the late fall of 1998. “When the exhibition ended I wanted to retain the impact the space had on viewers,” says Sublette. Entrance is through an arched doorway, above which are the words Men, Mountains, and Mesas and Dixon’s personal totem—a thunderbird enclosed in a circle. With approximately 1,200 square feet, the room is decorated with dark Mexican tile and cream-colored walls. Two large antique glass cases display letters written by Dixon, vintage photographs of him—some taken by Ansel Adams—and numerous books Dixon illustrated.

The room gives viewers a unique perspective on the life and work of one of the West’s most poignant painters. Dixon and his third wife, Edith Hamlin, or Edie as everyone called her, shut down his famous Montgomery Street studio in San Francisco in 1939 and departed for a new life in the Southwest. Their decision to relocate was prompted in part by changes in San Francisco’s art establishment. Furthermore, Dixon’s health had progressively worsened and they thought the warm Sonoran Desert climate would help. Then in his 60s, Dixon was losing his fight with emphysema. But perhaps most important for Dixon the artist was the inspiration he had found in the mystical desert lands of the Southwest since as early as 1900; the move promised freedom and renewal.

In November 1939, Dixon and Hamlin arrived in Tucson, where they rented a small house. Quickly, though, they decided to build their own home. By the spring of 1940 they had purchased two acres at the northern edge of Tucson from Gilbert Ronstadt, who would become their neighbor and close friend. Within six months, they had built a Mexican-colonial adobe home with a studio/living area, a spacious patio, two bedrooms, and a storeroom.

From their home, Dixon and Hamlin took painting trips to the Oodham reservation, the Sells annual rodeo southeast of Tucson, the old mining town of Bisbee, and places like Sonoita and Sasebe along the United States-Mexico border. Sometimes they would take friends down to Nogales to shop, then paint in the Santa Cruz Valley along the way home. Their wood-paneled Ford station wagon, with Dixons thunderbird motif painted on the sides, became a familiar sight in the region.

Hamlin has said they made many friends in Tucson, among them numerous members of the Ronstadt family. Once, near the end of Dixon’s life, they all assembled together one evening to serenade him with Mexican songs. Lengthy visits from artists and writers passing through Tucson—among them J. Frank Dobie, Ansel Adams, Winold Reiss, and Joseph Wood Krutchadded to their rich social life.

With Dixon increasingly confined to their home by 1945, the casa became a rendezvous for his friends. Around the invalid artist, who lounged in his characteristic long Chinese-style coat and Indian moccasins, gathered those who loved the man and his keen talk; his agile, youthful humor; and the easy hospitality of his home.

In those final Tucson years, Dixon gathered his remaining energy to pour into his art. He did a series of watercolors and wash-and-pen drawings that recorded graphic commentary on western life both old and new. The satiric Dixon humor surfaced when he poked fun at Tucson’s dude-ranch scene in other drawings.

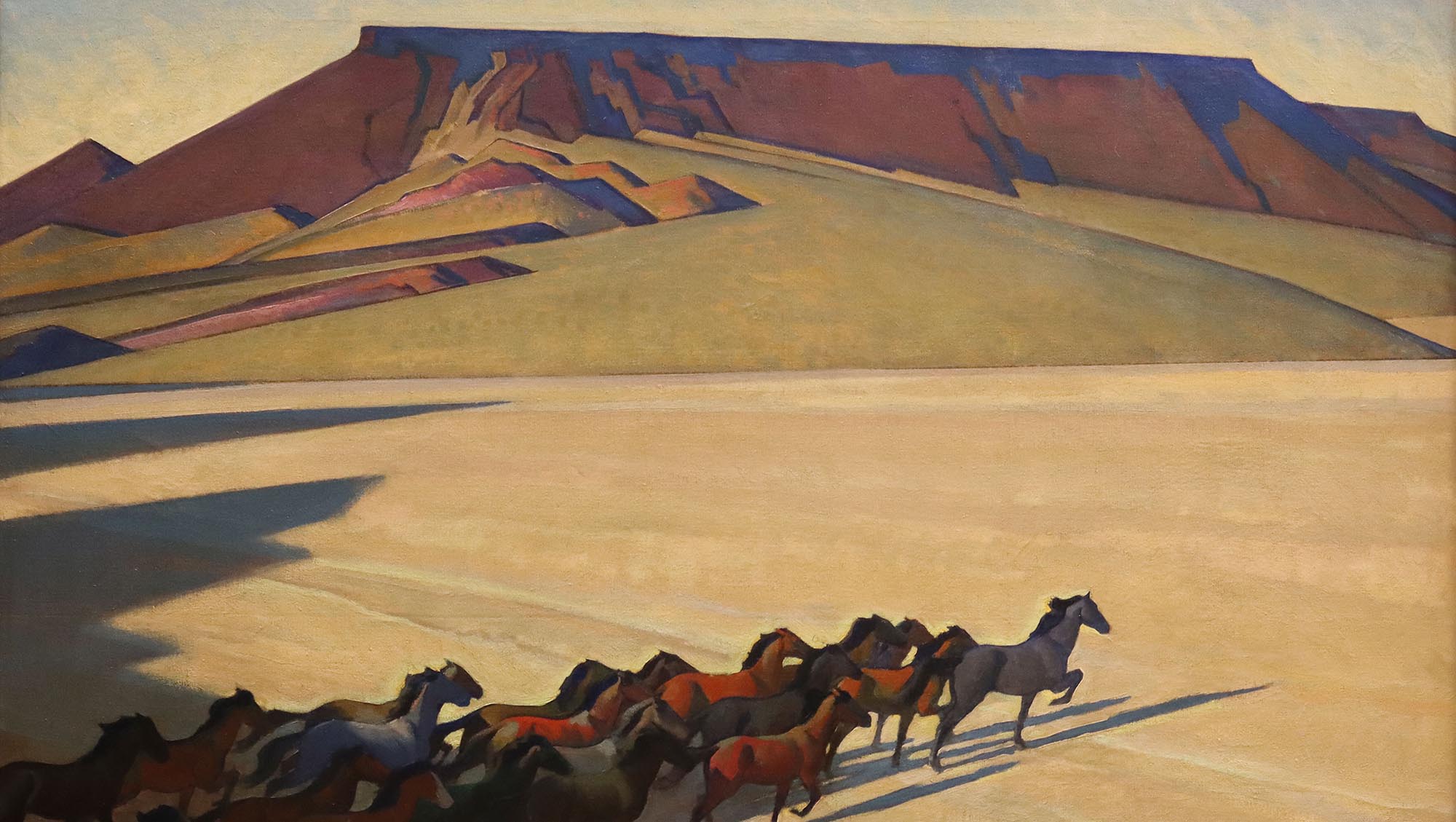

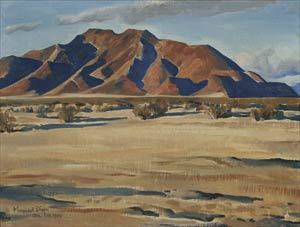

But always there were the paintings, drawn from the moods of Dixon’s beloved Southwest—everything from his interpretations of the azure skies and storms over Arizonas desert mountains to the remote mesas near his summer studio in Utah. In 1946, the Santa Fe Railway asked Dixon to design a mural of the Grand Canyon for its new city ticket office in Los Angeles. Although the attractive project seemed beyond his energies, he agreed to design the mural, directing his wife and two assistants in the execution of this striking work. Thus his work came to an end. On November 13, 1946, Dixon died in Tucson.

Desert Hills, Maynard Dixon

Desert Hills, Maynard Dixon

“Dixon is remembered today as one of the most original storytellers of the American West. To me, no painter has ever quite understood the light, the distances, the aboriginal ghostliness of the American West as well as Maynard Dixon,” writer Thomas McGuane once said. The great mood of his work is solitude, the effect of land and space on people. While his wok stands perfectly well on its claims to beauty, it offers a spiritual view of the West indispensable to anyone who would understand it.

His legend continues to inspire people like Mark Sublette. Trained as a physician with specialties in sports and preventive medicine, Sublette came to a personal crossroads seven years ago: Should he continue a promising career in medicine or pursue his deep interest in antique Native American art and western paintings?

“There was a choice between an important position with a professional sports organization—dealing with people—or dealing in art, [both of which] I truly love,” says Sublette. The need to take chances runs through the Sublette family history. Renowned mountain man and explorer William Sublette took one of the first wagon trains across the Oregon Trail, later pioneering what is called Sublette’ s Cutoff. Another Sublette opened the first trading post in Colorado. In 1992 Mark Sublette accepted a similar challenge when he decided to start his art gallery in Tucson. Since then, Sublette has expanded the original location to more than 10,000 square feet, opened two galleries in Santa Fe, and made plans to open a second location in Tucson. From the beginning, he wanted to specialize in Dixons work. “I saw my first Dixon painting while in medical school,” says Sublette. “His paintings remind me of the desert, particularly since I was born in New Mexico. Once I moved to Tucson it all seemed a natural connection.”

Sublette would like to see the Dixon room grow, viewing it as a good resource on the breadth and depth of Dixon and his art. “The response from people in Tucson has been overwhelmingly positive,” says Sublette. “I have had individualsnow in their 80s or 90swho personally knew Dixon in the early 1940s come in and respond to what they see in the room. Their memories of the man just tumble out.” The substantial space in the gallery dedicated to Dixons memory is something Sublette feels must be shared with Tucson, a place that welcomed and nurtured Maynard Dixon in the last years of his life.

Donald J. Hagerty, a frequent contributor to Southwest Art, writes extensively on western art. A revised edition of his book, Desert Dreams: The Art and Life of Maynard Dixon [Gibbs Smith, Publisher] was released in 1998.